The European Single Market: Expectations vs. Reality

When we think about the European Union, we think about three things: Brexit, Brexit, and Brexit. One of the most controversial and influential political moves by the United Kingdom in 2016 has sparked a wildfire of debate relating to the European Union’s questionable unity. The question is evident: Is the EU Single Market beneficial to the European Union?

The concept of unions is nothing out of the ordinary, with unions such as the Commonwealth, Nordic Councils, and Trans-Pacific partnership program, to name a few. But the European Union takes the word “Union” to a new level.

They are trying to create a single economic market throughout the union, with various financial agreements in areas such as goods, capital, services, and people, aiming to create a large single market (Cadman, 2017). The ultimate motive of creating such a union is to make peace between European countries by increasing their dependency on each other so the concept of war will not even stand in the spotlight.

As a result, the EU is, to some extent, successful in creating stable and vibrant economic growth in its member states. While the EU successfully developed newly joined nations with increased interdependency between the member states, economic integration also caused the EU to be fragile, as shown by the Greek Financial Crisis.

Economic Growth and Competitiveness

The European Union has seen steady GDP growth in the 21st century. The graph made by the European Commission shows the real GDP growth rate stabilized at around 2% per year, with forecasts stating that the development would continue in the foreseeable future (Moscovici, 2017).

The GDP growth for newer EU member states is even more vivid. For instance, the Baltic states, which include Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, gained their independence from the Soviet Union only in 1991. While the Baltics suffered an economic downturn initially, their economic reform caught up and was so rapid that the three countries only took around one decade to gain EU membership in 2004 (Staehr, 2017). After they joined the EU, their economic expansion further accelerated, with growth in Latvia averaging 11% (Bakker and Korczak, 2017). This growth rate is substantially quicker than most countries at the time, revealing how the European Union encourages economic development rapidly and vibrantly.

The booming economic reforms in the Baltic States are also because the European Commission prioritizes establishing solid diplomatic ties to Eastern Europe. Romano Prodi, the 10th president of the European Commission, claims that “After the fall of the Berlin Wall, it was clear that there was a hazardous gray area for the future of Europe, and that it was necessary to fill the vacuum as soon as possible.” (Jung, 2017). The European Union values political and economic stability in the European region and would try to assist newly formed countries to flourish under the influence of the EU’s solid and capitalistic single market.

However, some are skeptical of the single market, believing it inhibits the growth of more developed countries. The concern was made by the UKIP party during the Brexit campaign, stating that the United Kingdom gives 350 million pounds each week to other EU states (McCann and Morgan, 2016). While this claim is, to a certain extent, accurate regarding the fact that developed countries are losing money from sending money to other member states, the actual effect on the country’s economy is exaggerated. In fact, according to the World Bank, the GDP growth when comparing the EU, UK, France, and Germany shows that the growth of all these regions is relatively stable, averaging at about 2% (The World Bank, 2018). This debunks the theory that the single market inhibits more developed countries’ economic growth.

Focusing on creating stable and vibrant growth in Europe also led to long-lasting peace between the countries. The European Union has gained its fame as they have made peace in the continent previously plagued with war, with no significant intercontinental war ever since World War 2 ended in 1945. This is highly attributed to the European Union’s single market as the interdependency between nations has skyrocketed since the pre-EU days, making wars far less beneficial in the EU.

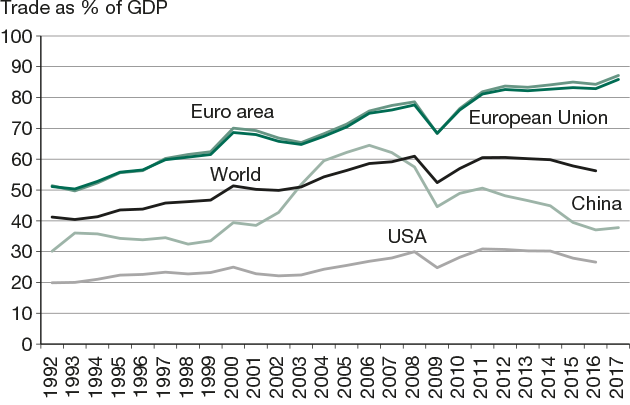

The interconnectivity between nations also made the European continent much more competitive in the global market, with growth surpassing the United States due to “A growing export market...modest inflation is but a few of the tailwinds that the Eurozone economy is experiencing,” as noted by economist Bert Colijn (Strupczewsk, 2017). This shows how the single market acted as a catalyst for economic growth and a method to develop peace within the EU and competitiveness outside of the EU with their exports.

The Sinking Ship

As the EU lifted barriers between European countries, it also opened up a floodgate that could destroy the entire European Union’s economy due to one leak. Even when the floodgate is sturdy, trying to unify an entire continent into one market is always a strong skepticism among many.

First, the Greek financial crisis is the perfect example of how the EU’s single market – specifically the Euro – is volatile. Before Greece joined the EU, the government was in massive debt due to its high inflation rate and poor economy (Hills, 2018). After they entered the EU, the economic problem became even less controllable as the Eurozone limited Greece’s control over its monetary policy. As the European Central Bank also controls Greece’s inflation rate, this causes Greece to have a much lower inflation rate than it should ideally have, making the deficit spiral out of control and causing the Greek Financial Crisis (Kindreich, 2017). This shows how the single market, in an attempt to unify the interest rate for all its member states, instead causes the problem to snowball until a breaking point.

While some may argue that this is a particular and dramatic case of when the single market harms the economy, it is still important to note that the EU’s attempt to unify the market is already filled with obstacles. For instance, in 1979, the EU took a step forward by removing trade barriers between countries by stating that if a product is legal in one country, it should also be permitted in another. This caused controversy with alcohol named crème de cassis, which was allowed in France but not in Germany as the level of alcohol content was over the regulation Germany had initially stated. In the end, under the European Court of Justice, the product can now be sold in Germany under mutual recognition (Chan, 2017). This act causes some to feel suppressed by the unifying market as it has undermined local regulations to secure its citizen’s health. This event, while less dramatic, still shows how, as the EU tries to push all its members into one unifying market, skepticism rises.

These events highlight a single market flaw: Full integration is impossible. Despite the positive intention of the single market, countries with vastly different economic regulations and policies can’t run under a single economy. This is also the primary concern leading to the rise in “Euro-skepticism” and other matters relating to destroying local cultures, immigration, and security (Hartleb, 2007). The single market is a ticking time bomb waiting to be detonated.