21 Lessons for the 21st Century by Yuval Noah Harari — Book Summary and Notes

In a world deluged by irrelevant information, clarity is power. How can insights about the distant past and future help us make sense of current affairs and of the immediate dilemmas of human societies?

In a world deluged by irrelevant information, clarity is power. How can insights about the distant past and future help us make sense of current affairs and of the immediate dilemmas of human societies?

In Sapiens, he explore our past. In Homo Deus, he looked to our future. Now, Yuval Noah Harari’s 21 Lessons for the 21st Century focuses on the here and now.

- Part 1 highlights the growing technological threats and dangers to humankind

- Part 2 examines a wide range of potential responses to human dilemmas.

- Part 3 explores whether humankind can rise to the occasion if we keep our fears under control.

- Part 4 questions whether if Homo sapiens are capable of making sense of the world it has created.

Part I: The Technological Challenge

Humankind is losing faith in the liberal story that dominated global politics in recent decades, exactly when the merger of biotech and infotech confronts us with the biggest challenges humankind has ever encountered.

1. Disillusionment

The End of History Has Been Postponed

Humans think in stories instead of in facts, numbers, or equations. The simpler the story, the better. During the 20th Century, the world formulated three grand stories that claimed to explain the past and to predict the future of the entire world: (1) the fascist story, (2) the communist story, and (3) the liberal story.

- The Fascist Story explained history as a struggle among different nations, and envisioned a world dominated by one human group that violently subdues all others

- The Communist Story explained history as a struggle among different classes, and envisioned a world in which all groups are united by a centralized social system that ensures equality even at the price of freedom.

- The Liberal Story explained explained history as a struggle between liberty and tyranny, and envisioned a world in which all humans cooperate freely and peacefully, with minimum central control even at the price of some inequality.

In 1938 humans were offered three global stories to choose from, in 1968 just two, in 1998 a single story seemed to prevail; in 2018 we are down to zero. To have one story is the most reassuring situation of all. Everything is perfectly clear. To be suddenly left without any story is terrifying. Nothing makes any sense.

In the past, we have gained the power to manipulate the world around us and to reshape the entire planet, but because we didn’t understand the complexity of the global ecology, the changes we made inadvertently disrupted the entire ecological system and now we face an ecological collapse. In the coming century biotech and infotech will give us the power to manipulate the world inside us and reshape ourselves, but because we don’t understand the complexity of our own minds, the changes we will make might upset our mental system to such an extent that it too might break down.

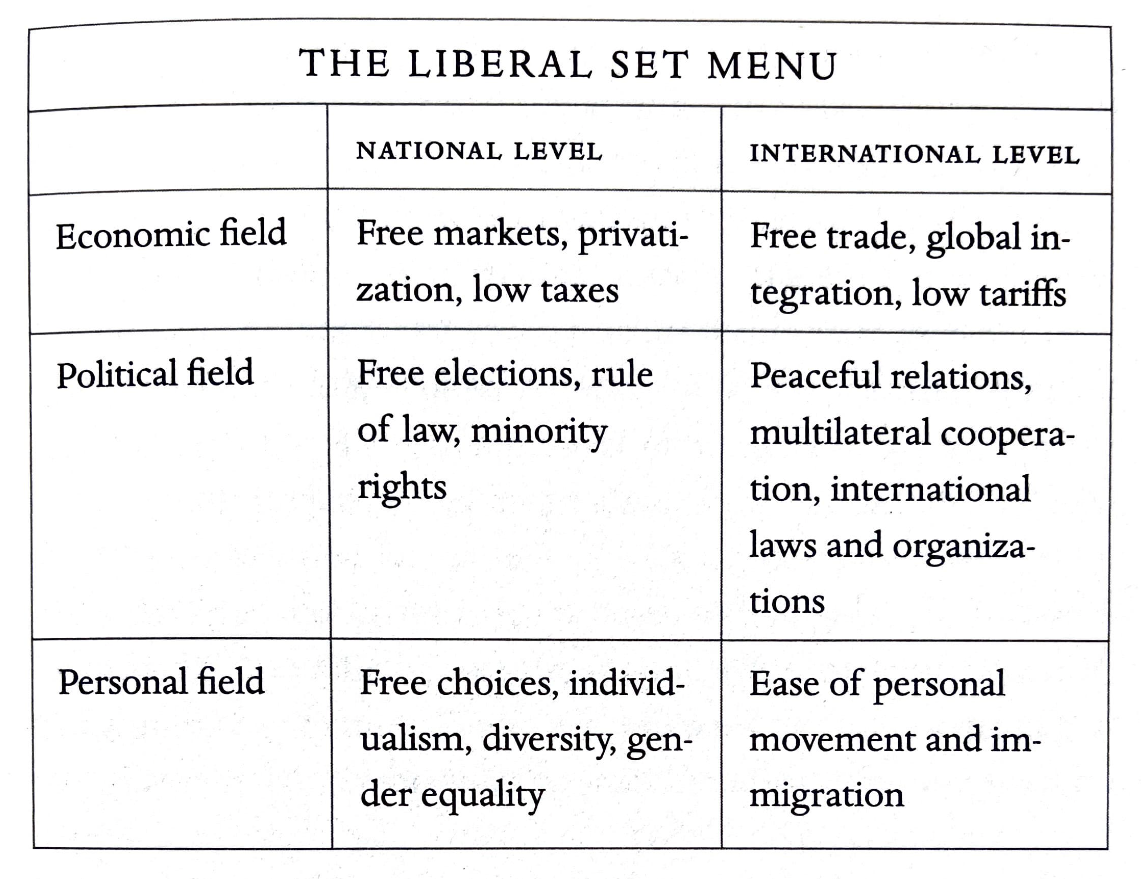

What we are seeing in recent years is not a complete abandonment of the liberal story. Rather, we are witnessing a shift from a “set menu approach” to a “buffet mentality”.

The liberal story argues that there are strong and essential links among the above six components. You can’t have one without the other because progress in one field both necessitates and stimulates progress in other fields. As for “anti-liberals”, none of them reject liberalism as a whole. Rather, they reject the set menu approach, and want to pick and choose their own dishes from a liberal buffet.

Perhaps the time has come to make a clearn break with the past and craft a completely new story that goes beyond not just the old nations but even the core modern values of liberty and equality.

2. Work

When You Group Up, You Might Not Have A Job

Humans have two types of abilities – physical and cognitive. In the past, machines competed with humans mainly in raw physical abilities, while humans retained an immense edge over machines in cognition. However, AI is now beginning to outperform humans in more and more of these skills, including in the understanding of human emotions. It is uncertain whether humans will ever retain a secure edge beyond these two fields of activity.

AI can be better at jobs that demand intuitions about other people. Many forms work require the ability to correctly assess the emotions and desires of others. As long as such emotions and desires are generated by an immaterial spirit, it seems obvious that computer can never replace them. Yet if these emotions and desires are merely biochemical algorithms, there is no reason compouters cannot decipher them—and do so far better than any Homo sapiens.

AI might help create new human jobs in another way. Instead of competing with AI, we could focus on servicing and lervaging AI. If so, the job market of 2050 might well be characterized by human-AI cooperation rather than competitions. By 2050, not only the idea of a job for life but even that of a profession for life might seem old-fashioned.

The key questions are: what to do in order to prevent jobs from being lost; what to do in order to create enough new jobs; and what to do if, despite our best efforts, job losses significantly outweigh job creation.

3. Liberty

Big Data Is Watching You

The liberal story cherishes human liberty as its number one value. It argues that all authority ultimately stems from the free will of individual humans, as it is expressed in their feelings, desires and choices. In politics, liberalism believes that the voter knows best. It therefore upholds democratic elections. In economics, liberalism maintains that the customer is always right. It therefore hails free-market principles. In personal matters, liberalism encourages people to listen to themselves, be true to themselves, and follow their hearts – as long as they do not infringe on the liberties of others.

What will happen to this view of life as we increasingly rely on AI to make decisions for us? At present we trust Netflix to recommend us new series, and Google Maps to choose whether to turn right or left. But once we begin to count on AI to decide what to study, where to work, and who to marry, human life will cease to be a drama of decision-making.

Imagine you bought a new car, but before you can start using it, you must open the settings menu and choose one of two options in case of an emergency. The Altruist sacrifices its owner to the greater good, whereas the Egoist does everything in its power to save its owner, even if it means killing more pedestrians. Is this a choice you want to make?

In general, there are three possibilities we need to consider:

- Consciousness is somehow linked to organic biochemistry such that it will never be possible to create consciousness in non-organic systems.

- Consciousness is not linked to organic biochemistry, but it is linked to intelligence such that computers could develop consciousness, and computers will have to develop consciousness if they are to pass a certain threshold of intelligence.

- There are no essential links between consciousness and either organic biochemistry or high intelligence. Computers could become super-intelligent while still having zero consciousness.

Digital dictatorships are not the only danger awaiting us. All wealth and power might be concentrated in the hands of a tiny elite, but most people will suffer not from exploitation, but from something far worse – irrelevance.

4. Equality

Those Who Own the Data Own the Future

Throughout history the rich and the aristocracy always imagined that they had superior skills to everybody else, which is why they were in control. As far as we can tell, this wasn’t true. The average duke wasn’t more talented than the average peasant – he owed his superiority only to unjust legal and economic discrimination. However, by 2100, the richest 1% might own not only most of the world’s wealth, but also most of the world’s beauty, creativity, and health. The two processes together—bioengineering coupled with the rise of AI—might therefore result in the separate of humankind into a small class of superhuman and a massive underclass of Homo sapiens.

The race to obtain the data is already on, headed by data giants such as Google, Facebook, Baidu, and Tencent. So far, many of these giants seem to have adoped the business model of “attention merchants”. They capture out attention by providing us with free information, services, and entertainment. Then, they sell our attention to advertisers. Yet the data giants are most likely aiming for something worth more than any advertising revenue; we aren’t their customers—we are their product.

This data hoard opens a path to a radically different business model whose first victim will be the advertising industry itself. The new model is based on transferring authority from humans to algorithms, including the authority to choose and buy things. Once algorithms choose and buy things for us, the traditional advertising industry will go bust. Consider Google. Google wants to reach a point where we can ask it anything, and get the best answer in the world. What will happen once we can ask Google, ‘Hi Google, based on everything you know about cars, and based on everything you know about me (including my needs, my habits, and my views on global warming) – what is the best car for me?’ If Google can give us a good answer to that, and if we learn by experience to trust Google’s wisdom instead of our own easily manipulated feelings, what could possibly be the use of car advertisements?

Private ownership one one’s personal data may sound more attractive, but it is unclear what it actually means. How does one regulate the ownership of data? We know how to build a fence around a field, assign a gate at the gate, and control who goes in or out. However, we don’t know what it means to protect something intangible that’s out there everywhere and nowhere simultaneously?

Part II: The Political Challenge

The merger of infotech and biotech threatens the core modern values of liberty and equality. Any solution to the technological challenge has to involve global cooperation. But nationalism, religion and culture divide humankind into hostile camps and make it very difficult to cooperate on a global level.

5. Community

Humans Have Bodies

Zuckerberg claims that Facebook is committed “to continue improving our tools to give you the power to share you experience with others.” Yet what people really need are the tools to connect with their personal experiences. In reality, people are encouraged to understand themselves in terms of how others see it. If something intriguing happens, the gut instinct of social media users is to pull out their smartphones, take a picture, post it online, and wait for the “likes” and “comments” to start flooding in. In turn, they barely ever notice what they feel themselves, as what they feel is increasingly determined by online reactions.

On an even deeper level, biometric sensors and direct brain–computer interfaces aim to erode the border between electronic machines and organic bodies to literally get under our skin. Once the tech-giants come to terms with the human body, they might end up manipulating our entire bodies in the same way they currently manipulate our eyes, fingers and credit cards. We may come to miss the good old days when online was separated from offline.

6. Civilization

There is Just One Civilization in the World

According to the “clash of civilizations” thesis, humankind has always been divided into diverse civilizations whose members view the world in irreconcilable ways. Identity is defined by conflicts and dilemmas more than agreement. People still have different religions and national idities, but when to comes to the practical stuff, almost all of us belong to the same civilization. For all the national pride people feel when their delegation wins a gold medal and their flag is raised, there is far greater reason to feel pride that humankind is capable of organising such an event.

7. Nationalism

Global Problems Need Global Answers

The whole of humankind now constitutes a single civilization with all people sharing common challenges and opportunities. Yet Americans, Britons, and Russians increasingly support nationalistic isolation. Could this be the solution to the unprecedented problems of our global world?

The Nuclear Challenge: As long as humans know how to enrich uranium and plutonium, their survival depends on privileging the prevention of nuclear war over the interests of any particular nation. Zealous nationalists who cry “Our Country first!” should ask themselves whether their country by itself, without a robust system of international cooperations, can protect the world—or even itself—from nuclear destruction.

The Ecological Challenge: An atom bomb is such an obvious and immediate threat that nobody can ignore it. Global warming, in contrast, is a more vague and protracted menace. Whenever long-term environmental considerations demand some painful short-term sacrifice, nationalists might be tempted to put immediate national interests first, and reassure themselves that they can worry about the environment later, or just leave it to people elsewhere.

The Technological Challenge: Traditionally, nuclear confrontations resembled a hyper-rational chess game. What would happen when players could use cyberattacks to wrest control of a rival’s pieces, when anonymous third parties could move a pawn without anyone knowing who is making the move – or when AlphaZero graduates from ordinary chess to nuclear chess?

Patriotism is about taking care of your compatriots, and in the 21st Century, you must cooperate with foreigners in order to take good care of your compatriots. So good nationalists should now be globalists. To globalise politics implies that political dynamics within countries and even cities should give far more weight to global problems and interests.

When the next election comes along, and politicians implore you to vote for them, ask these politicians four questions:

- If you are elected, what actions will you take to reduce the risks of nuclear war?

- What actions will you take to reduce the risks of climate change?

- What actions will you take to regulate disruptive technologies, such as AI and bioengineering?

- And finally, how do you see the world of 2040? What is the worse-case scenario, and what is your vision for the best-case scenario?

8. Religion

God Now Serves the Nation

The true expertise of pritests and gurus has always been interpretation. A priest is somebody who knows how to justify why the rain dance failed, and why we must keep believing our god even though he seems deaf to our prayers. Yet it is precisely their genius for interpretation that puts religious leaders at a disadvantage when they compete against scientists. Scientists too know how to cut corners and twist the evidence, but in the end, the mark of science is the willingness to admit failure and try a different tack. That’s why scientists gradually learn how to grow better crops and make better medicines, whereas priests and gurus learn only how to make better excuses.

Human power depends on mass cooperation, mass cooperation depends on manufacturing mass identities – and all mass identities are based on fictional stories, not on scientific facts or even on economic necessities. This collision between global problems and local identities manifests itself in the crisis that now besets the greatest multicultural experiment in the world.

9. Immigration

Some Cultures Might Be Better Than Others

Though globalisation has greatly reduced cultural differences across the planet, it has simultaneously made it far easier to encounter strangers and become upset by their oddities. To clarify matters, it would perhaps be helpful to view immigration as a deal with three basic conditions or terms:

- Term 1: The host country allows the immigrants in.

- Term 2: In return, the immigrants must embrace at least the core norms and values of the host country, even if that means giving up some of their traditional norms and values.

- Term 3: If the immigrants assimilate to a sufficient degree, over time they become equal and full members of the host country. ‘They’ become ‘us’.

These three terms give rise to three distinct debates about the exact meaning of each term. A fourth debate concerns the fulfilment of the terms.

- Debate 1: The first clause of the immigration deal says simply that the host country allows immigrants in. But should this be understood as a duty or a favour? Is the host country obliged to open its gates to everybody, or does it have the right to pick and choose, and even to halt immigration altogether?

- Debate 2: The second clause of the immigration deal says that if they are allowed in, the immigrants have an obligation to assimilate into the local culture. But how far should assimilation go? If immigrants move from a patriarchal society to a liberal society, must they become feminist? If they come from a deeply religious society, need they adopt a secular world view?

- Debate 3: The third clause of the immigration deal says that if immigrants indeed make a sincere effort to assimilate – and in particular to adopt the value of tolerance – the host country is duty-bound to treat them as first-class citizens. But exactly how much time needs to pass before the immigrants become full members of society?

- Debate 4: On top of all these disagreements regarding the exact definition of the immigration deal, the ultimate question is whether the deal is actually working. Are both sides living up to their obligations?

When evaluating the immigration deal, both sides give far more weight to violations than to compliance. Do we enter the immigration debate with the assumption that all cultures are inherently equal, or do we think that some cultures might well be superior to others?

No matter what conclusion the regime reaches, two key points should be borne in mind: First, it would be wrong for any government to force large-scale immigration on an unwilling local population. Absorbing immigration is a difficult long-term process, and to successfully integrate immigrants you must have the support and cooperation of the location population. Second, though citizens have a right to oppose, they should realize that they still have obligations towards foreigners. We are living in a global world, and whether we like it or not our lives are interwined with the lives of people on the other side of the world.

Part III: Despair and Hope

Though the challenges are unprecendented, and though the disagreements are intense, humankind can rise to the occasion if we keep our fears under control and be a bit more humble about our views.

10. Terrorism

Don’t Panic

Terrorists are masters of masters of mind control. They kill very few people but nevertheless manage to terrify billions and rattle huge political structures. Diabetes and high sugar levels kills up to 3.5 million people annually, while air population kills about 7 million per year. So why do we fear terrorism more than sugar, and why do governments lose elections because of sporadic terrorist attacks but not failure to tackle chronic air pollution?

Terrorism is a military strategy that hopes to change the political situation by spreading fear rather than by causing material damage. Though it leaves all the important decisions in the enemy’s hands, they present the state with an impossible challenge of its own: to prove that it can protect all of its citizens from political violence, anywhere, anytime.

Fear and confusion causes the enemy to misuse their intact strength and overreact. Terrorists don’t think like army generals; they think like theatre producers. A terrorist is like a gambler who is holding a bad hand and tries to convince his rivals to reshuffle their cards. He cannot lose anything, and he could win everything.

11. War

Never Underestimate Human Stupidity

Why is it so difficult for major powers to wage successful wars in the 21st Century? In the past, economic assets were mostly material; therefore, it was relatively straightfoward to enrich oneself by conquest. Yet in the 21st Century only puny profits can be made that way. Today the main economic assets consist of technological and institutiona knowledge rather than wheat fields, gold mines, or even oil fields.

The golden age of conquerers warfare was a low-damage, high profit air. Nuclear warfare and cyberwarfare, by constrast, are high-damage, low-profiting technologies. You could use such tools to destroy entire countries but not to build profitable empires. How we can make nations, religions, and cultures more realistic and modest about their true place in the world?

12. Humility

You Are Not The Centre of the World

Most people tend to believe they are the centre of the world, and their culture is the linchpin of human history.

Scientists suggest that morality in fact has deep evolutionary roots before humankind. All social mammals adapted by evolution to promote group cooperation. For example, when wolf cubs play with one another, they have ‘fair game’ rules. If a pup bites too hard, or continues to bite an opponent that has rolled on his back and surrendered, the other pups will stop playing with him. In Chimpanzee bands, dominant members are expected to respect the property rights of weaker members. If a junior female chimpanzee finds a banana, even the alpha male will usually avoid stealing it for himself.

13. God

Don’t Take the Name of God in Vain

Does God exist? That depends on which God you have in mind: the cosmic mystery, or the worldly lawgiver? We invoke this mysterious God to explain the deepest riddles of the cosmos? Why is there something rather than nothing? We do not know the answers to these questions, and we give our ignorance the grand name of God.

On other occasions people see God as a stern and worldly lawgiver, about whom we know only too much. We know exactly what He thinks about fashion, food, sex and politics, and we invoke this Angry Man in the Sky to justify a million regulations, decrees and conflicts.

When the faithful are asked whether God really exists, they often begin by talking about the enigmatic mysteries of the universe and the limits of human understanding. ‘Science cannot explain the Big Bang,’ they exclaim, ‘so that must be God’s doing.’ Yet like a magician fooling an audience by imperceptibly replacing one card with another, the faithful quickly replace the cosmic mystery with the worldly lawgiver.

Though gods can inspire us to act compassionately, religious faith is not a necessary condition for moral behavior. The idea that we need a supernatural being to make us act morally assumes that there is something unnatural about morality. Morality doesn’t mean “following divine commands”. It means “reducing suffering”. If you really understand how an action causes unnecessary suffering to yourself or to others, you will naturally abstain from it.

Every violent act in the world begins with a violent desire in somebody’s mind, which disturbs that person’s own peace and happiness before it disturbs the peace and happiness of anyone else. Long before you murder anyone, your anger has already killed your own peace of mind.

14. Secularism

Acknowledge Your Shadow

What does it meant to be secular? Secularism is sometimes referred to as the negation of religion, and secular people are therefore characterized by what they don’t believe and don’t do. However, few people would adopt such a negative identity.

Self-professing secularists view secularism in a different way. The most important secular commitment is to the truth, which is based on observation and evidence rather than on mere faith. Seculars strive not to confuse truth with belief. What happens when an action hurts one person but helps another? When secular people encounter such dilemmas, they do not ask “What does God command?” Rather, they weigh carefully the feelings of all concerned parties, examine a wide range of observations and possibilities, and search for a middle path that will cause as little harm as possible.

Secular people cherish scientific truth: not in order to satisfy their curiosity, but in order to know how best to reduce the suffering in the world. It takes a lot of courage to fight biases and oppressive regimes, but it takes even greater courage to admit ignorance and venture into the unknown. Secular education teaches us that if we don’t know something, we shouldn’t be afraid of acknowledging our ignorance and looking for new evidence. Even if we think we know something, we shouldn’t be afraid of doubting our opinions and checking ourselves again.

The secular world judges people on the basis of their behaviour rather than of their favourite clothes and ceremonies. A person can follow the most bizarre sectarian dress code and practise the strangest of religious ceremonies, yet act out of a deep commitment to the core secular values. Secular education teaches us to distinguish truth from belief; to develop our compassion for all suffering beings; to appreciate the wisdom and experiences of all the earth’s denizens; to think freely without fearing the unknown; and to take responsibility for our actions and for the world as a whole.

Every religion, ideology and creed has its shadow, and no matter which creed you follow you should acknowledge your shadow and avoid the naïve reassurance that ‘it cannot happen to us’. Secular science has at least one big advantage over most traditional religions, namely that it is not terrified of its shadow, and it is in principle willing to admit its mistakes and blind spots. If you believe in an absolute truth revealed by a transcendent power, you cannot allow yourself to admit any error – for that would nullify your whole story. But if you believe in a quest for truth by fallible humans, admitting blunders is an inherent part of the game.

If you want your religion, ideology, or worldview to lead the world, my first question to you is: “What was the biggest mistake your religion, ideology, or worldview committed? What did it get wrong?”

Part IV: Truth

If you feel overwhelmed and confused by the global predicament, you are on the right track. Global processes have become too complicated for any single person to understand. How then can you know the truth about the world, and avoid falling victim to propaganda and misinformation?

15. Ignorance

Your Know Less Than You Think

The power of groupthink is so pervasive that it is difficult to break its hold even when its views seem to be rather arbitrary. People rarely appreciate their ignorance, because they lock themselves inside an echo chamber of like-minded friends and self-confirming newsfeeds, where their beliefs are constantly reinforced and seldom challenged.

Worst still, great power inevitably distorts the truth. The problem of groupthink and individual ignorance besets not just ordinary voters and customers, but also presidents and CEOs. Each word is made extra heavy upon entering your orbit, and each person you see tries to flatter you, appease you, or get something from you. They know you cannot spare them more than a minute a two, and they are fearful of saying something improper or muddled, so they end up saying either empty slogans or the greatest clichés of all.

Leaders are thus trapped in a double bind. If they stay in the centre of power, they will have an extremely distorted vision of the world. If they venture to the margins, they will waste too much of their precious time. As Socrates observed more than 2,000 years ago, the best we can do under such conditions is to acknowledge our own individual ignorance.

16. Justice

Our Sense of Justice Might Be Out of Date

Justice demands not just a set of abstract values, but also an understanding of concrete cause-and-effect relations. The system is structured in such a way that those who make no effort to know can remain in blissful ignorance, and those who do make an effort will find it very difficult to discover the truth. How is it possible to avoid stealing when the global economic system is ceaselessly stealing on my behalf and without my knowledge? The problem is that it has become extremely complicated to grasp what we are actually doing.

Most of the injustices in the contemporary world result from large-scale structural biases rather than from individual prejudices, and our hunter-gatherer brains did not evolve to detect structural biases. We are all complicit in at least some such biases, and we just don’t have the time and energy to discover them all. As Harari says, “Writing this book brought the lesson home to me on a personal level. When discussing global issues, I am always in danger of privileging the viewpoint of the global elite over that of various disadvantaged groups. The global elite commands the conversation, so it is impossible to miss its views. Disadvantaged groups, in contrast, are routinely silenced, so it is easy to forget about them – not out of deliberate malice, but out of sheer ignorance.”

Even if we truly want to, most of us are no longer capable of understanding the major moral problems of the world. In trying to comprehend and judge moral dilemmas of this scale, people often resort to one of four methods.

- To downsize the issue; to imagine conflict between the bad and the good

- To focus on a touching human story, which ostensibly stands for the whole conflict

- To weave conspiracy theories

- To create a dogma, putting our trust in some allegedly all-knowing theory, institution or chief, and follow it wherever it leads us.

17. Post-Truth

Some Fake News Lasts Forever

We are repeatedly told these days that we are living in a new and frightening era of ‘post-truth’, and that lies and fictions are all around us. In fact, humans have always lived in the age of post-truth. Homo sapiens is a post-truth species, whose power depends on creating and believing fictions.. As long as everybody believes in the same fictions, we all obey the same laws and can thereby cooperate effectively.

In practice, the power of human cooperation depends on a delicate balance between truth and fiction. When most people see a dollar bill, they forget that it is just a human connection. As they see the green piece of paper with the picture of a dead white man, they see it as something valuable in and of itself. They hardly ever remind themselves, “Actually, this is a worthless piece of paper, but because other people view it as valuable, I can make use of it.”

Humans have a remarkable ability to know and not know at the same time. More accurately, they can know something when they really think about it, but most of the time they don’t think about it. Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi propaganda maestro explains his method succinctly: “A lie told once remains a lie, but a lie told a thousand times becomes the truth.”

Truth and power can travel together only so far. Soon or later, they go their separate paths. If you want power, at some you point you will have to spread fictions; if you want to know the truth, at some point you will have to renounce power.

It is our responsibility to invest time and effort in uncovering our biases and in verifying our sources of information. We cannot investigate everything, but it is precisely this fact that we need to carefully investigate our favorite sources of information.

- If you want reliable information, pay you good money for it. If you get your news for free, you might well be the product. It is absurd to give up your attention for free in exchange for low-quality information. If you are willing to pay for high-quality food, clothes, and cars—why aren’t you willing to pay for high-quality information?

- If some issues seems exceptionally important to you, make the effort to read the relevant scientific literature.

Silence isn’t neutrality; it is supporting the status quo.

18. Science Fiction

The Future is Not What You See in the Movies

One theme that science fiction has explored with far greater insight concerns the danger of technology being used to manipulate and control human beings. The Matrix depicts a world in which almost all humans are imprisoned in cyberspace, and everything they experience is shaped by a master algorithm. The Truman Show focuses on a single individual who is the unwitting star of a reality TV show. Unbeknownst to him, all his friends and acquaintances – including his mother, his wife, and his best friend – are actors.

However, both movies – despite their brilliance – in the end recoil from the full implications of their scenarios. They assume that the humans trapped within the matrix have an authentic self, which remains untouched by all the technological manipulations, and that beyond the matrix awaits an authentic reality, which the heroes can access if they only try hard enough.

The current technological and scientific revolution implies not that authentic individuals and authentic realities can be manipulated by algorithms and TV cameras, but rather that authenticity is a myth. People are afraid of being trapped inside a box, but they don’t realise that they are already trapped inside a box – their brain – which is locked within a bigger box – human society with its myriad fictions. When you escape the matrix the only thing you discover is a bigger matrix. When the peasants and workers revolted against the tsar in 1917, they ended up with Stalin; and when you begin to explore the manifold ways the world manipulates you, in the end you realise that your core identity is a complex illusion created by neural networks.

Since your brain and your ‘self’ are part of the matrix, to escape the matrix you must escape your self. Escaping the narrow definition of self might well become a necessary survival skill in the twenty-first century.

Part V: Resilience

How do you live in an age of bewilderment, when the old stories have collapsed, and no new story has yet emerged to replace them?

19. Education

Change is the only constant

How can we prepare ourselves and our children for a world of such unprecedented transformations and radical uncertainties? In such a world, the last thing a teacher needs to give her pupils is more information. They already have far too much of it. Instead, people need the ability to make sense of information, to tell the difference between what is important and what is unimportant, and above all to combine many bits of information into a broad picture of the world.

Many pedagogical expertise argue that schools should switch to teaching ‘the four Cs’ – critical thinking, communication, collaboration and creativity. More broadly, schools should downplay technical skills and emphasise general-purpose life skills. Most important of all will be the ability to deal with change, to learn new things, and to preserve your mental balance in unfamiliar situations. Teachers themleves usually lack the mental flexibility of the 21st Century because they were products of the old educational system. In order to keep up with the world of 2050, you will need not merely to invent new ideas and products – you will above all need to reinvent yourself again and again. Change itself is the only certainty.

20. Meaning

Life is Not a Story

Who am I? What should I do in life? What is the meaning of life? Humans have been asking these questions from time immemorial. Every generation needs a new answer, because what we know and don’t know keeps changing. What is the best answer we can give today?

If we cannot leave something tangible behind – such as a gene or a poem – perhaps it is enough if we just make the world a little better? A wise old man was asked what he learned about the meaning of life. “Well,” he answered, “I have learned that I am here on earth in order to help other people. What I still haven’t figured out is why the other people are here.”

While a good story must give me a role, and must extend beyond my horizons, it need not be true. A story can be pure fiction, and yet provide me with an identity and make me feel that my life has meaning. If you ask for the true meaning of life and get a story in reply, know that any story is wrong, simply for being a story. Most stories are held together by the weight of their roof rather than by the strength of their foundations. The exact details don’t really matter. The universe does not just work like a story.

So why do people believe in fictions? People are taught to believe in stories from early childhood. By the time their intellect matures, they are so heavily invested in the story, that they are far more likely to use their intellect to rationalise the story than to doubt it. Most people who go on identity quests are like children going treasure hunting: they find only what their parents have hidden for them in advance.

Of all rituals, sacrifice is the most potent. Once you suffer for a story, it is ususally enough to convince you that a story is real. This is of course a logical fallacy, and it works in the consumer economy too. Why do you think women ask their lovers to bring them diamond rings? Once the lover makes such a huge financial sacrifice, he must convince himself that it was for a worthy cause. The sacrifice is not just a way to convince your lover that you are serious – it is also a way to convince yourself that you are really in love.

It is our own human fingers that wrote the Bible, the Quran and the Vedas, and it is our minds that give these stories power. They are no doubt beautiful stories, but their beauty is strictly in the eyes of the beholder. We hope to find meaning by fitting ourselves into some ready-made story about the universe, but according to the liberal interpretation of the world, the truth is exactly the opposite. The universe does not give me meaning. I give meaning to the universe. This is my cosmic vocation.

21. Meditation

Just Observe

Self-observation has never been easy, but it might get progressively harder with time. As history unfolds, we create more and more complex stories about ourselves that we lose sight of who we really are. For a few more years or decades, we still have a choice. If we make the ffort, we can still investigate who we really are. But if we want to make use of this opportunity, we had better do it now.