Stanislavski's System: A Modern Approach to Stage Acting

The Stanislavski method is a group of techniques actors use to embody the character and present themselves naturally and realistically onstage.

The History of Konstantin Stanislavsky

Konstantin Stanislavski was a Russian theatre practitioner who developed the Stanislavski Method. Stanislavski was born in January 1863 in Moscow, Russia. He was part of the Alekseives family, who had a strong passion for Theatre: his father was a manufacturer who constructed a theatre stage for their family, and his mother was a French actress’s daughter.

Stanislavski’s real name was Konstantin Sergeevich Alexeyev; he used the name “Stanislavski” to hide his theatre productions from his parents. Becoming an actor was challenging for someone in his social class; actors had a low social status throughout 19th-century Russia. Nonetheless, after his father approved his work, he became one of the most notable contributors to the Theatre.

Prominent Works

In 1898, Stanislavski founded the influential Moscow Art Theatre with Vladimir Nemiorich-Danchenko. It was a location for Naturalistic Theatre, compared to the melodramas that were Russia’s most popular form of Theatre in the 19th Century. Naturalistic Theatre was a 19th-century theatrical movement that sought to portray real life on stage. Stanislavski was a committed follower of Naturalistic Theatre through his life’s work.

Stanislavski had a habit of taking careful notes and evaluating his work. He wrote three volumes of The Acting Trilogy: An Actor Prepares, Building a Character, and Creating a Role. His books are a semi-fictional story from a junior actor’s perspective who receives coaching from Stanislavski, known as Tortsov in the story.

- An Actor Prepares investigates the inner preparation of the Stanislavski method.

- Building a Character reviews the external techniques of acting: physicalization and vocalization.

- Creating a Role explains the precautions of performing regarding Gogol’s The Inspector General and Shakespeare’s Othello.

The Acting Trilogy also serves as a guide for the readers’ acting skills. As Charlie Chaplin said, The Acting Trilogy “helps everyone reach out for big dramatic art. It tells what an actor needs to rouse the inspiration he requires for expressing profound emotions.”

Stanislavski's Principles of Acting

Before Stanislavski’s method was developed, an actor’s role was to portray specific gestures, facial expressions, and language according to the director’s demands. However, this approach resulted in irrational acting that lacked emotion. Konstantin Stanislavski saw the need for a change and developed the Stanislavski method.

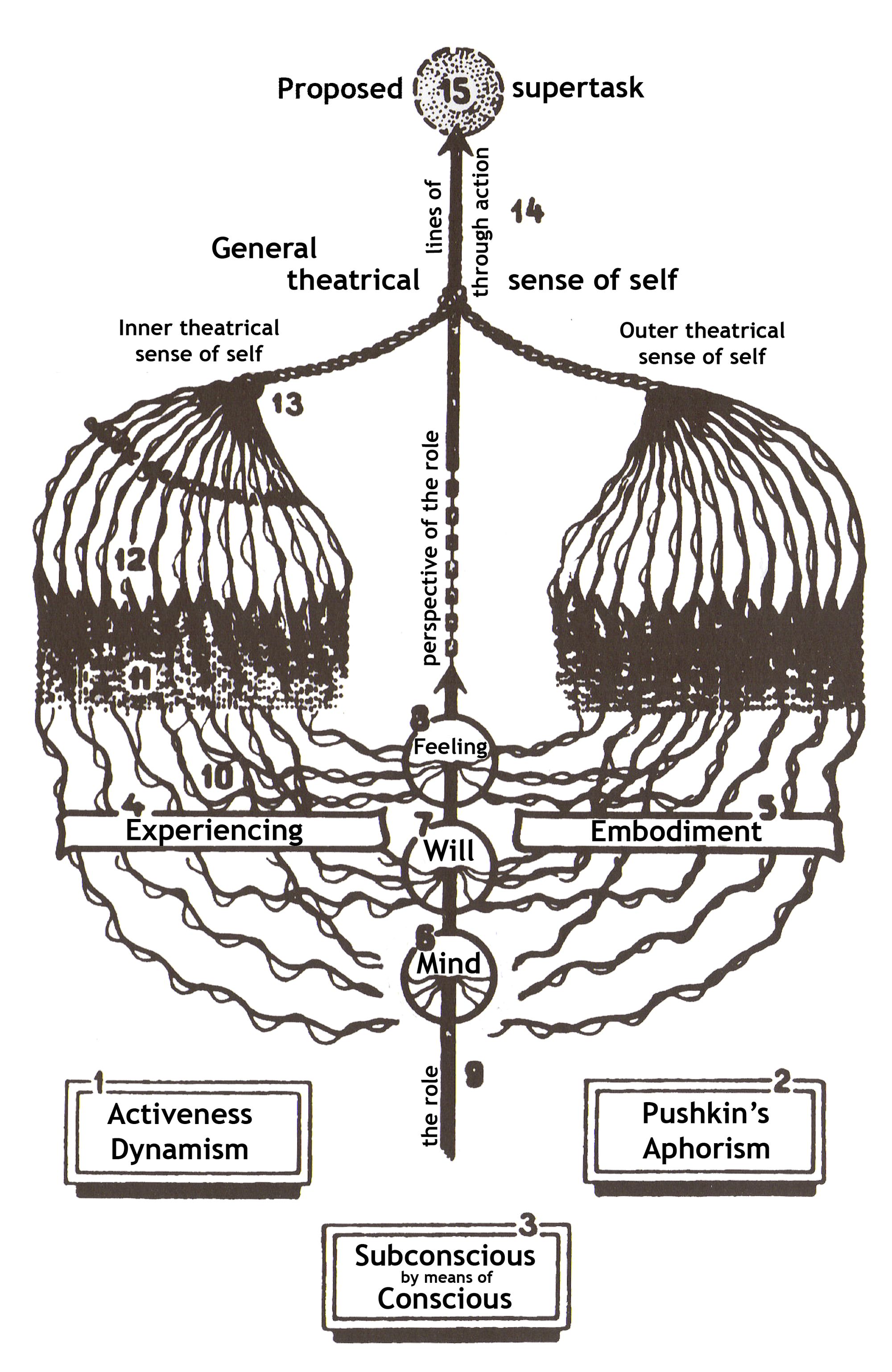

The Stanislavski method is a group of techniques actors use to embody the character and present themselves naturally and realistically onstage. The system cultivates the “art of experiencing”, which incorporates the balance of “experiencing and embodiment” to bring the actor closer to the character’s authentic emotional experiences.

Super Objectives

Scene objectives and super-objectives are some of the techniques in Stanislavski’s method. Scene objectives are the character’s goals within each scene of the play. It guides the characters through the story by stimulating them to overcome challenges to reach their goal.

Stanislavski theorized that objectives should direct every decision a nature makes. the actor should discover the character’s current goal in each scene, which should be “action-oriented” to “encourage character interaction onstage”. Thus, a helpful objective should justify an actor’s actions and build characterization.

The through-line is the direction that takes the character from their starting point to reach their super-objective. As Stanislavski describes, the super-objective is the “objective of all objectives.” It connects all the character’s objectives from scene to scene. It is the “spirit of the writer” that “inspired them to write and which inspires an actor to act.” Therefore, the actor should also discover the character’s overall goal. An effective super-objective should be the character’s ultimate drive.

Given Circumstances

Stanislavski’s Given Circumstances helps actors identify the character’s general characteristics and behavior. The Given Circumstances include any detail the playwright or author specified in the story. The actors should examine the dialogue and stage directions to collect information concerning the characters’ status, personality, history, and physical characteristics. The actors should also consider how the design elements of Theatre, including the sets, lighting, sound, and costumes, help convey the character’s traits.

Once the actor determines the Given Circumstances, the actor begins to identify the Subtext, which is the meaning behind the character’s speech and actions. Actors must ask themselves, “What is the playwright trying to convey with his work?” The actor can communicate subtle meaning to the audience through pauses, intonation, and gestures. “Keep in mind that a person says only ten percent of what lies in his head; ninety percent remains unspoken,” Stanislavski says.

The Magic "If"

Stanislavski’s “Magic If” depicts an ability to envision the consequences of oneself in Given Circumstances. The actor asks a “what if” question to discover aspects of the character’s back story or present situation, which are not directly given but hinted at in the play.

Sharon Marie Carnicke, a professor of Theatre, warns: “It is easy to misunderstand this notion as a directive to play oneself”; “Placing oneself in the role does not mean transferring one’s circumstances to the play, but rather incorporating into oneself circumstances other than one’s own.” Therefore, the actors should ask themselves “what if” questions regarding “What would the character do in this situation?” instead of “What would I do?”. In rehearsal, the actors develop an imaginary stimulus of “inner objects” to support the “unbroken line” in a performance. An “unbroken line” is the actor’s capability to concentrate on the character’s fictional world and overcome distractions from the audience, the camera crew, or thoughts relating to the actor’s personal life.

Relaxation

Relaxation is another technique in Stanislavski’s method. Relaxation aims to identify the excessive tension in the body and eliminate it to remain focused on the object of attention. Stanislavski believed that tension is the actor’s “occupational disease.” “Muscular tautness interferes with the inner emotional experience. As long as you have physical tenseness, you cannot even think about delicate shadings of feeling or the spiritual life of your past.”, Stanislavski said. For actors, “tension” uses unnecessary muscles, thoughts, and energy.

Lee Strasberg was one of the three founding members of the Group Theatre who popularised Stanislavski’s method. He invented Strasberg’s Relaxation Exercise, which aims to help the actor locate and relax the unnecessary tension in their body. The neck is the most common area of tension, and the face is the region of mental tension. Using an armless chair with a straight back, the actor rests in a sleeping position.

The actor begins by taking deep breaths. Next, the actors ask themselves, “Where am I mentally now?”. The purpose is not to contain emotional responses but to let them live throughout the exercise. The actor is encouraged to release the tension in their voice by releasing a long, sustained “ah” sound. The “ah” sound starts low in volume and intensity and gradually increases. The actor then stretches their arm above their head, slowly moving the fingers, wrists, and associates to find tense muscles. When tension is found, the power has to release it and relax the muscles. For facial muscles, the actor has to move their lips, stick their tongue out and rotate it in circles, extend and shift their jaw in different directions, and move their brow up and down. The accumulation of unspoken thoughts and emotions is believed to create continual shapes of tension in the facial muscles. This process continues in every force, from the fingers to the toes. Finally, the actor returns to their original position. It is recommended that the actor repeats this exercise for about 30 to 60 minutes.

While the actor is practicing Strasberg’s Relaxation Exercise, the training also strengthens their concentration. Humans struggle to focus for long periods as we are drawn to short-term mental or sensual satisfaction. Strasberg’s Relaxation Exercise enables actors to stop worrying about their lives by releasing the physical tension in their body muscles and mental stress in their facial muscles. His training allows actors to immerse into the story’s world and embody the character more extensively.

Emotional Memory

Emotional memory requires an actor to recall an experience with a similar emotion to the character and ‘borrow’ these feelings. The goal of dynamic memory is to create authenticity in performance and bring the role to life. However, the actor must learn to control their emotions and only apply the sentiment of the experience to the character’s context. If actors cannot separate themselves from their memories, they can break from their role if it is traumatic.

In the chapter “Emotional Memory” of An Actor Prepares, Stanislavski writes, “Never lose yourself on stage. Always act as yourself, as an artist. You can never get away from yourself. The moment you lose yourself on stage marks the departure from truly living your part and the beginning of exaggerated false acting.” (p177). Sense memory can help actors to achieve this. Instead of solely recalling the emotion, sense memory requires an actor to relive the sight, hearing, touch, smell, and taste of the experience.

Strasberg developed the coffee cup exercise to practice sensory memory: the actor fills a coffee cup with their preferred coffee and explores each sensory aspect of the coffee and the cup in as much detail as possible. First, the actor begins exploring one of the five senses. The actor should answer as many questions as possible regarding the sense. For example, sight: “What is the pattern on the coffee cup? What does it remind you of?”, “What are the dimensions of the cup?”, “What materials is the cup made of?”. This process is repeated for each of the five senses. The coffee cup exercise aims to practice concentration and imagining the five senses. Therefore, the actor can picture the sensory details of their emotional memories.

“When you develop a belief in yourself through the re-creation of sensory reality, then you can begin to create a truthful, believable life for the character you’re portraying,” said Dianne Hull and Lorrie Hull from the Hull Actors Studio.

Communion

During a performance, an actor may worry about the judgment and criticism by the audience. The actor cannot maintain character when the brain is focused on the audience’s response. Therefore, the audience can change an actor’s performance who is not concentrated in the character’s world.

“Public solitude” is a concept created by Stanislavski that refers to the actor’s ability to appear “private in public.” When the actor is on the stage, he is in public, but the actor should appear in his private space. The actor should not join the audience; the audience should join the actor. The intimate moment exercise was designed to remove the audience’s impact on an actor: the actor conducts personal activities on stage that they would generally stop doing if other people watched.

For example, they can perform their favorite dance that would be considered ridiculous by the public. With practice, the actors will become less embarrassed or uncomfortable doing their private activities in public. The concentration required to have an intimate moment in public empowers the actor to take more risks and embody a character’s actions that may be viewed as socially unacceptable.

Famous Actors who use Stanislavsky's System

Prominent actors trained in the Stanislavski method include Marlon Brando and Robert De Niro. To prepare for The Men, Brando stayed in a hospital bed at the Birmingham Army Hospital for a month to get in the injured veteran’s mindset that he would be playing. Brando refused director Stanley Kramer’s good intentions to let him stay in a hotel, “he insisted on living with the paraplegics in Birmingham Veterans Hospital during the four weeks before production began.” Strauss wrote. “This, he felt, was necessary to give a completely knowledgeable and valid performance in his role. He was given a bed in a 32-bed ward, where he was treated almost like any other patient”.

For Taxi Driver, De Niro acquired a taxi driver’s license and labored 12-hour shifts as a taxi driver for a month. During breaks in the film’s shootings, he would pick up passengers in New York City. Martin Scorsese, the director of Taxi Driver, said, “Bob (De Niro) was very instrumental because he pointed out to me that the first line of dialogue was ‘Turn off the meter’”.

In A Nutshell: Stanislavsky's System

Stanislavski never wanted his method to codify acting. He encouraged actors to “make up something that will work for you! But keep breaking traditions” (A Quote by Konstantin Stanislavski). And that was what his best followers, like Lee Strasberg, did. Stanislavski’s method supplied a road map for investigating the “conscious road to the gates of the unconscious, which is the foundation of modern theatre. And it is a map that no actor, even today, can afford to ignore”, said Michael Billington, a British author and art critic.