The Psychology of Money by Morgan Housel — Book Summary and Notes

In what other industry does someone with no college degree, training, background, formal experience, and connections massively outperform someone with the best education, training, and contacts?

5 Lessons in 60 Seconds

In what other industry does someone with no college degree, training, background, formal experience, and connections massively outperform someone with the best education, training, and contacts?

In The Psychology of Money, Housel uses the lenses of psychology and history to convince readers that soft skills are just as, if not more important, than the technical side of money.

- To grasp why people bury themselves in debt, you don’t need to study interest rates; you must learn the history of greed, insecurity, and optimism.

- To get why investors sell out at the bottom of a bear market, you don’t need to study the math of expected future returns; you need to think about the agony of looking at your family and wondering if you are investments are imperilling their future.

“History never repeats itself;

man always does.”

The Psychology of Money

Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness By Morgan Housel

No One’s Crazy

Your personal experiences with money make up maybe 0.00000001% of what’s happened in the world but maybe 80% of how you think the world works.

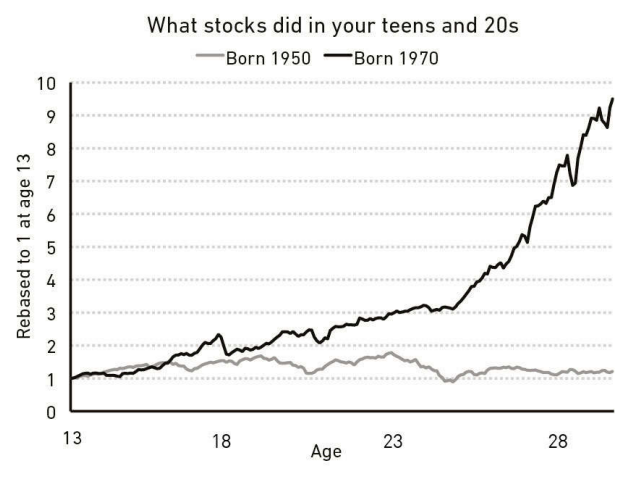

People do some crazy things with money, but no one is crazy. People from different generations, raised by different parents who earned different incomes and held different values in different parts of the world, born into different economics, experiencing different job markets with different incentives and different degrees of luck, learn very different lessons.

Studying history makes you feel like you understand something. However, you may not understand it enough to change your behavior until you’ve lived through it and personally felt its consequences. As investor Michael Batnick says, “Some lessons must be experienced before they can be understood.” We are all victims, in different ways, of that truth.

- People’s lifetime investment decisions are heavily anchored to the experiences those investors had in their generation. If you happened to grow up when the stock market was strong, you invested more of your money in stocks later in life compared to those who grew up when stocks were weak.

Every decision people make with money is justified by taking the information they have at the moment and plugging it into their unique mental model of how the world works. Those people can be misinformed. They may have imperfect information. They may have no idea what they're doing. However, every financial decision a person makes makes sense to them and checks their boxes.

Take a simple example: Lottery Tickets.

Who buys them? Mostly poor people. Those buying $100 in lottery tickets are the same people who claim they can't afford $100 for an emergency. They are blowing their safety nets on something with 1 in 1,000,000 odds of making it big.

It seems unbelievable from our perspective, but most of us are likely not in the lowest-income group. Imagine it from their perspective:

"We live paycheck-to-paycheck, and saving seems out of each. Our prospects for higher wages seem out of reach. We can't afford nice vacations, cars, health insurance, or homes in safe neighborhoods. We can't afford our kids to go to college without crippling debt. We don't have much of the stuff you people who read finance books either have now or have a good chance of obtaining. Buying a lottery ticket is the only time we can dream of the good stuff we already have and take it for granted. We are paying for a dream, and you may not understand that because you are already living your dream. That's why we buy more lottery tickets than you do."

Luck and Risk

Nothing is as good or bad as it seems.

Luck and Risk are siblings—the forces that guide every outcome in life other than personal effort. You are one person in a game with seven billion other people and infinite moving parts. The accidental impact of actions outside your control can be more consequential than the ones you actively take.

Bill Gates was 13 years in 1968 when he went to one of the only high schools in the world that had a computer, Lakeside School. The story of how Lakeside School even got a computer is remarkable.

Bill Dougall was a World War II Navy pilot turned high school math and science teacher. “He believed that book study wasn’t enough without real-world experience”, recalled Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen. In 1968, Dougall petitioned the Lakeside School Mothers’ Club to use the proceeds from its annual rummage sale (about $3,000) to lease a Teletype Model 30 computer hooked up to the General Electric mainframe terminal for computer time-sharing.

Start with 303 million, and end with 300. One in a million high school students attended the high school that had the combination of cash and foresight to buy an advanced computer. Gates is not shy about what this meant: “If there had been no Lakeside, there would have been no Microsoft”, he told the school’s graduating class in 2005.

Gates is staggeringly intelligent, even more hardworking, and as a teenager, had a vision for computers that even most seasoned computer executives couldn’t grasp. He also had a 1 in 1,000,000 head start by attending Lakeside school.

Luck and Risk are so hard to measure, so hard to accept, and so often overlooked. For every Bill Gates, there is a Kent Evans who was just as skilled and driven but ended up on the other side of life roulette.

If you give Luck and Risk their proper respect, you realize that when judging people’s financial success—both your own and others’—it’s never as good or as bad as it seems.

Key Takeaways

- Be careful who you praise and admire. Be careful who you look down upon and wish to avoid becoming.

- Therefore, focus less on specific individuals and more on broad patterns.

Never Enough

When rich people do crazy things

John Bogle, the Vanguard founder, once told a story about money that highlights something we don’t think about enough:

At a party given by a billionaire on Shelter Island, Kurt Vonnegut informs his pal, Joseph Heller, that their host, a hedge fund manager, had made more money in a single day than Heller had earned from his wildly famous novel Catch-22 over its whole history. Heller responds, “Yes, but I have something he will never have… enough.”

The question we should as is why someone worth hundreds of millions of dollars would be so desperate for more money that they risked everything in pursuit of even more.

As Warren Buffet puts it: "To make money they didn’t have and didn’t need, they risked what they did have and did need. And that’s foolish. It is just plain foolish. If you risk something important to you for something unimportant to you, it just does not make any sense."

The social comparison ceiling is so high that almost no one will ever hit it. It’s a battle that can never be won, or the only way to win is not to fight it. “Enough” is realizing that an insatiable appetite for more will push you to the point of regret.

Key Takeaways

- The most challenging financial skill is getting the goalpost to stop moving.

- Social comparison is the problem here.

- “Enough” is not too little.

- There are many things never worth risking, no matter the potential gain.

Confounding Compounding

$81.5 billion of Warren Buffet’s $84.5 billion net worth came after 65th birthday. Our minds are not built to handle such absurdities.

Lessons from one discipline can often teach us something important about unrelated fields. Warren Buffet is a phenomenal investor but had he started investing and retired in his 60s; few people would have heard of him. Effectively all of Buffett’s financial success can be linked to the financial longevity he maintained in his senior years.

What if he spent his teens and 20s exploring the world and finding his passion, and by age 30, his net worth was $25,000? Let’s assume he earned the same extraordinary annual investment returns (22% annually), but quit investing and retired at age 60. What would be a rough estimate of his net worth today?

Not $84.5 billion. $11.9 million.

His skill is investing, but his secret is time.

Getting Wealthy vs. Staying Wealthy

Good investing is not necessarily about making good decisions. It’s about consistently not screwing up.

There are millions of ways to get wealthy, but only one way to stay wealthy: a combination of frugality and paranoia.

The Survival Mindset

- “More than I want significant returns, I want to be financially unbreakable. If I’m indestructible, I can stick around long enough for compounding to work wonders.

- Planning is essential, but the most important part of every plan is to plan on the plan not going according to plan.

- A barbell personality—optimistic about the future but paranoid about what will prevent you from getting to the future

Tails, You Win

You can be wrong half the time and still make a fortune.

How could anyone have foreseen, early in life, what were to become the most sought-after works of the century? You could say “skill.” You could say “luck.” The investment firm Horizon Research has a third explanation: “The greatest investors bought vast quantities of art.”

The great art dealers operated like index funds. They bought everything they could and bought it in portfolios, not individual pieces they happened to like. Perhaps 99% of the works were of little value, but that doesn’t matter if the other 1% was the work of someone like Picasso.

Out of more than 21,000 venture financings from 2004 to 2014:

- 65% lost money

- 2.5% made 10-20x returns

- 1% made 20-50x returns

- 0.5% made 50x or more returns. That’s where the majority of the industry’s returns come from.

Napoleon’s definition of a military genius was “The man who can do the average thing when all those around him are going crazy.”

Most financial advice is about today. What should you do now, and what stocks look like good buys today? However, most of the time, today is not all that important.

Over your lifetime as an investor, the decisions you make today or tomorrow will not matter nearly as much as what you do during the small number of days when everyone else around you is going crazy.

Freedom

Controlling your time is the highest dividend your money pays

The highest form of wealth is the ability to wake up every and say, “I can do whatever I want today.” Many people want to become wealthier to make them happier, but there’s a common denominator—people want to be the authors of their lives.

Money’s most fantastic intrinsic value is its ability to give you control over your time. According to Angus Campell, having a strong sense of controlling one’s life is a more dependable predictor of well-being than any objective conditions of life we have considered.

Man in the Car Paradox

No one is impressed with your possessions as much as you are.

People want to use wealth to signal to others that they should be well-liked and admired. Those other people often bypass admiring you, not because they don’t think wealth is admirable, but because they use your wealth as a benchmark for their desire to be liked and respected.

Housel writes a letter to his to soon-to-be born son:

“You might think you want an expensive car, a fancy watch, and a huge house. But I’m telling you, you don’t. You want respect and admiration from others and think having expensive stuff will bring it. It seldom does—especially from the people you want to respect and admire you.

Wealth is What You Don’t See

Spending money to show people how much you have is the fastest way to have less money.

Rich is a current income. Wealth is hidden. Its value lies in offering you options, flexibility, and growth to one day purchase more intangible stuff than you could right now.

Save Money

The only factor you can control generations of the only things that matter. How wonderful.

Building wealth has little to do with your income or investment returns and lots to do with your savings rate. More importantly, the value of wealth is relative to fulfilling your needs.

Think about how much time and effort goes into outperforming index funds by 0.1% when we can exploit several percentage points of lifestyle bloat in one's finances with less effort.

- Savings can be created by spending less.

- You can spend less if you desire less.

- And you will desire less if you care less about what others think about you.

You don't need a specific reason to save. You can save just for saving's sake. And indeed, you should. Everyone should.

Be Reasonable, Not Rational

Aiming to be mostly reasonable works better than trying to be coldly rational.

You’re not a spreadsheet. You’re a person: a screwed-up, emotional person.

When viewed through a strictly financial lens, investing has a social component people often ignore. The historical odds of making money in U.S markets are over 50/50 over on-day periods, 68% in one-year periods, 88% in 10-year periods, and (so far) 100% in 20-year periods.

If you view “do what you love” as a guide to a happier life, it sounds like empty fortune cookie advice. Suppose you view it as providing the endurance necessary to put the quantifiable odds of success in your favor. In that case, you realize it should be the most crucial part of any financial strategy.

Surprise!

History is the study of change, ironically used as a future map.

Scott Sagan advises everyone who follows the economy to hang on their wall: “Things that never happened before happen all the time.”

History is the study of change, but investors and economists often use it as an unassailable guide to the future. Do you see the irony?

Many investors are far into the trap of over-relying on “past data as a signal to future conditions in a field where innovation and change are the livelihoods of progress”. We often use events like the Great Depression and World War II as a benchmark for worst-case scenarios when considering future investment returns. However, those record-setting events had no precedent when they occurred. It’s a massive pool of people making imperfect decisions with imperfect information about things that will enormously impact their well-being.

“The four most dangerous words in investing are, ‘it’s different this time.” — John Templeton.

The further back in history you look, the more general your takeaways should be.

Room For Error

The most important part of every plan is planning on your plan not going according to plan.

There is never a moment when you’re so right that you can bet on every chip before you. Take risks to get ahead, but no risk that can wipe you out entirely is ever worth taking. You have to survive to succeed. The ability to do what you want, when you want, for as long as you want, has an infinite ROI.

You’ll Change

Long-term planning is more complex than it seems because people’s goals and desires change over time.

“At every stage of our lives, we make decisions that will profoundly influence the lives of the people we’re going to become, and when we become those people, we’re not always thrilled with the decisions we made. Young people pay good money to get tattoos removed that teenagers paid good money to get. Middle-aged people rush to divorce people, and young adults rush to marry. Older adults work hard to lose what middle-aged adults work hard to gain. On and on and on.” — Daniel Gilbert.

As Charlie Munger says, "the first rule of compounding is never unnecessarily interrupting it." We should come to accept the reality of our changing goals and desires. The quicker it’s done, the sooner we can return to compounding.

Nothing’s Free

Everything has a price, but not all prices are labeled.

Every job looks easy when you’re not doing it because the challenges someone faces in the area are often invisible to the crowd.

Why do so many people willing to pay the price of houses, luxurious vacations, and consumer goods try so hard to avoid paying the price of good investment returns? Here’s the thing: The price of investing success is not immediately obvious. Like everything worthwhile, successful investing demands a price, not money, but fear, doubt, and uncertainty of the unknown. These are the admission costs for the prospect of greater returns than low-fee bonds.

You'll never enjoy the magic if you view the admission fee as a fine. So define the cost of success and be ready to pay for it.

You and Me

Beware of taking financial cues from people playing a different game than you are.

Investors often mistakenly take cues from other investors who are playing a different game than they are. Assets have one rational price in a world where investors have different financial goals and time horizons.

- Are you looking to cash out within ten years?

- Are you looking to sell within a year?

- Are you a day trader?

So much of consumer advice is subtly influenced by people you admire and do because you subtly want people to respect you. However, while we can see how much money people spend on homes, clothes, and vacations, we don’t see their goals, worries, and aspirations.

The Seduction of Pessimism

Optimism sounds like a sales pitch. Pessimism sounds like someone trying to help you.

- Tell someone everything will be great, and they’re likely to shrug you off or give you a skeptical look.

- Tell someone that they’re in danger and you have their undivided attention.

As John Stuart Mill writes, “I have observed that no the man who hopes when others despair, but the man who despairs when others hope, is admired by a large class of people as a sage.”

Only 2.5% of Americans owned stocks on the eve of the Stock Market Crash in 1929, which sparked the Great Depression. However, the world watched as the market collapsed, wondering what it signals about their fate.

As historian Eric Rauchway writes: “This fall in value immediately afflicted only a few Americans. But so closely had the others watched the market and regarded it as an index of their fates that they suddenly stopped much of their economic activity.”

Progress happens too slowly to notice, but setbacks happen too quickly to ignore.

When You'll Believe Anything

Why stories are more powerful than statistics.

The more you want something to be true, the more likely you are to believe a story that overestimates the odds of it being true. Investing is one of the only fields that offers daily opportunities for extreme rewards. Everyone has an incomplete worldview, but we form a complete narrative to fill the gaps.

In Why Don't We Learn From History, Lindell Hart writes:

"History cannot be interpreted without the aid of imagination and intuition. The sheer quantity of evidence is so overwhelming that selection is inevitable. Where there is selection, there is art. Those who read history tend to look for what proves them right and confirms their personal opinions. They defend loyalties. They read to affirm or to attack. They resist inconvenient truths since everyone wants to be on the side of the angels. Just as we start wars to end all wars."

Daniel Kahneman once laid out the path these stories take:

- When planning, we focus on what we want and can do, neglecting the plans and skills of others whose decisions might affect our outcomes.

- We focus on the causal role of skills and neglect the part of luck in explaining the path and predicting the future.

- We focus on what we know and neglect what we do not know, which makes us overly confident in our beliefs.

A start-up's outcome depends on its competitors' achievements and changes in the market as well as on its own efforts. However, entrepreneurs naturally focus on what they know best—their plans and actions and the most immediate threats and opportunities, such as funding availability. They know less about their competitors and therefore find it natural to imagine a future in which the competition plays little part.

All Together Now

What we’ve learned about the psychology of your own money.

- Go out of your way to find humility when things are going right and seek compassion when they go wrong.

- Less ego, more wealth.

- Manage your money in a way that helps you sleep at night.

- Increase your time horizon

- You can be wrong half the time and still make a fortune

- Use money to gain control over your time

- You don’t need a specific reason to save.

- Define the cost of success and be ready to pay for it.

- Worship room for error and avoid the extremes of financial decisions.

- Define the game you’re playing.